“you directly etch, that is, scratch with a needle, right into the celluloid, or paint right onto the celluloid so that the color sticks to it. … you can … create motions under control in a sequential way which ends up looking okay. But if you also synchronize the visual accenting with sound accenting of music with say, a rhythmic beat, then you've got something you can look at. The visual image … is a combination of abstract shapes wiggling around synchronized with the abstract sound or music you hear. One enhances the other, one sharpens up the other.” [17]

In a sense he was one of the earliest moving-image makers (by which I mean both film and video makers) to have attempted to produce a visual music directly onto film. As such he presages the work of the Ubu film-makers and the work of those video artists for whom synthetic video and visual music were important early forms. For his films Lye used a multitude of shapes and lines which might have been scratched, stencilled or painted onto the film surface presenting mobile geometric shapes in a flow of bright colour. Many of these elements came to stand for the sound of a particular instrument and danced or vibrated according to the kind of sound that instrument made. For example a saxophone was represented by a “thick vertical line” that broke up “into clusters of fibres” or a guitar became a horizontal line that would quiver and twang. [18]

A Colour Box (1935) consists in a background laid down with paint through a variety of dot screens – of the type used in printing photographs in books – plus the occasional geometric object impressed onto the surface, usually as some sort of mask to the painted background, plus single or multiple wiggling vertical lines and other squiggles painted to represent and synchronize with the timing of the instruments: percussion, string base, trumpet, piano and mandolin, played by a classic dance band of the time. Towards the end a series of frames of text announce the costs of parcel post with the British Post Office. “For music, he used a piece played by Don Baretto and his Cuban Orchestra. The film was shown widely and won a prize at the 1935 Brussels Film Festival.” [19]

A later GPO film, Rainbow Dance (1936) is a combination of live action and painted and scratched film. The live action is usually used as a colour mask. The film begins with rain over mountain ranges seen in pastel colours in the background. The rain is a series of diagonal lines painted on the frame. The “camera” tilts down to a man in a raincoat who is standing in the rain at the entrance of an ally with his umbrella held high. He is seen in flat solid colours. When the rain has stopped a rainbow appears opposite him and he closes his umbrella only to be swept away by a couple of asterisks and taken on a holiday. The man, now in holiday clothes of flat solid colours, dances and leaps over the landscape. He goes to the seaside which is made from cut-out fishes, sail-boat masks and scratched wavy lines. The countryside is seen in a series of pastels consisting of maps and then mountains followed by a tennis court, where he plays tennis and dances off into a village represented by a single house, a road that was once the tennis court paving stones, and trees at the side of the road. He then rests from all his exertion. It's all an ad for the Post Office Savings Bank, the Brighton (Beach) branch of course.

Overall, Lye sought to express an empathy between the perceiving body, the musical instruments of the soundtrack and the movement of lines, shapes and colours on the screen echoing the density and variations in pitch and harmonics of the sounds of the instruments.

Now, in the early 1960s Australia was culturally isolated but the Australian government was greatly in support of American adventurism in Vietnam and the cinema was swamped by the populism of Hollywood. The visual arts were dominated by two strongly inter-connected debates, one over style and the other over regionalism. The question of style was deeply associated with a vociferous debate as to whether Australian art was merely parochial in its realism and should thus take on a greater recognisance of international styles as represented particularly by abstraction; or whether it should be seen as a manifestation of a national identity responding to, for example, the harsh qualities of the landscape and thus maintain the figurative modernism of the Antipodeans. [20] This debate raged to and fro for many years, well into the 1980s, [21] with the leading art critic of the 1960s, Bernard Smith, arguing for the figurative and against abstraction. [22] However in the later years of that decade, abstraction made substantial inroads within Australia through exhibitions like Two Decades of American Painting that toured here in 1967 and The Field at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1968, and by journals like Studio International out of Britain.

It felt, to many outside the debates over style in painting, that Australia’s isolation ought not be preserved. The so called “cultural cringe” [23] could only be defeated by “being unself-consciously ourselves” [24] thus promoting a kind of art that in its own internal strength would stand with the work of the rest of our international peers. Within the universities in Sydney, where a small group of students took an independent stance, exposure to European avant-garde traditions in theatre and film as well as experimental attitudes in architecture [25] began to produce a new experimental culture outside of the traditional visual arts. With the appearance of the satirical Oz magazine in April 1963, produced by Martin Sharp, Richard Neville, Richard Walsh and with graphical contributions by Mick Glasheen and Sharp, a confident, irreverent political and social reappraisal of the culture was launched. This was the real beginning of the 60s in Australia. [26] At the same time the university film societies were showing new animation, including the work of the Canadian animator, Norman McLaren, and Len Lye, as well as the films of the European and (by the late 1960s) the American avant-garde.

Albie Thoms and Ubu Films

Meanwhile, videotape was just becoming available in Australia in the form of the 2-inch quadruplex machine developed by Ampex in the US in 1965. Albie Thoms, who in 1965 was studying theatre at the University of Sydney and working as a production trainee at the ABC, tells his part in the story:

“In 1965 I was employed as a production trainee at ABC television, and I was introduced to video tape recording processes using 2-inch Ampex machines. Basically they were just using this to record programs at that stage. “In the subsequent year, they acquired a couple more – ended up having about four machines, but originally they only had a couple. In ‘66 I was assistant producer on a comedy show called Nice and Juicy. The producer was a guy named Eric Tayler who, though he had worked at the BBC for years and obviously videotaped a lot of his programs, wasn’t at all au fait with videotape editing. And because I’d been introduced to the possibility of that as part of my training, I then became the person that … Well first of all, he started recording the program as a continuous run, a half hour comedy show. It was a dismal failure. It was pointed out to him that he could videotape it in segments and improve the performances and correct the mistakes and things. And because he wasn’t au fait in video, and I’d just had a little bit of training, I then became the person that assembled the programs from the video segments that he recorded. And we were using the big Ampex machine, big as a bloody refrigerator almost, and we had to use 10 to zero countdowns, and there was no electronic editing.

An avant-garde theatre was also developing. While working at the ABC in 1965 Thoms was producing The Theatre of Cruelty, his “review of European avant-garde theatre” [29] for the Sydney University Dramatic Society (SUDS). [30] He asked David Perry to shoot two films for him. One was a version of The Spurt of Blood, an Artaud script which required some apparently magical effects, and the other was a version of Schwitters’ Poem 25, in which a series of frames with numbers were written directly onto film stock. [31] This led to the beginning of their collaboration as Ubu Films, with Perry shooting Thoms’ films as well as his own. Also in the production crew was Aggy Read who was the stage mechanist. Shortly after The Theatre of Cruelty performance, on August 28, 1965, [32] Thoms, Perry, Read and John Clark established Ubu Films, named after Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi. [33]

Ubu Films became a production and exhibition group that was occasionally wildly controversial, regularly attracted the opprobrium of the Commonwealth Film Censor for the nudity and sexual freedom of their films, and variously excited and bored their audiences with an astonishing range of work. [34] However their role was not merely absurdist and subversive given that their leadership in the underground culture meant that to a large extent the period of the later 1960s became the era of experimental film in Australia. This was also stimulated by seasons like the 1967 touring exhibition of American avant-garde film, "New American Cinema" [35], in much the same way that "Two Decades of American Painting" provoked Australian visual art. [36] There were also two articles on underground films, one in Time (1967) [37] and one in Newsweek (1967) [38] “that legitimised [Ubu’s] work and encouraged widespread experiment”. [39]

Ubu Films turned out to have been a most important development in non-commercial film-making in Australia; leading to the Sydney Film-makers Co-op and generally encouraging the re-development of an interest in locally made films in Australia. They supported the exhibition of experimental and avant-garde film in general, distributing films offered to them by the likes of Frank Eidlitz, Ludwig Dutkiewicz and Stan Ostoja-Kotkowski [40] while also taking on Australian distribution of some of the American avant-garde film introduced to Australia through the Sydney Film Festivals and the New American Cinema program. Ubu ran for five years, branching into light-shows for the happenings that had become a part of the hippie scene in Sydney.

Thoms had been making his feature length abstract film Marinetti since December 1967. [41] It begins with a long sequence of black frames with an increasing number of white frames intercut every minute and a voice-over in which Thoms and others (among them David Perry) discuss the Futurists and their impact on art and many aspects of popular culture – it is almost as if Thoms is explaining his approach to the film – until the white frames predominate. Gradually John Sangster's music (a strong contemporary jazz) and the chatter of a party take over the soundtrack and we are slowly, very slowly, presented with actual images as a room fills with people, at which point the film cuts to the party on the verandah of a Paddington terrace house interspersed with the occasional shot of a near naked woman relaxing as the party gets started. It was filmed hand-held and begins in a day-to-day manner with people in the Ubu office downstairs, the lounge room and the backyard of the house. As it develops it becomes increasingly psychedelic.

Since it was an Australian film Marinetti did not have to be submitted to the NSW film censor, and it premiered at the Wintergarden Theatre in Rose Bay, on June 17, 1969. A capacity audience turned up, but, being an abstract and very avant-garde film, not at all like the irreverent work of most Ubu films, it was not well received. There was an angry and negative response which “resulted in a virtual riot” [42] at the cinema and the press coverage over the next few days was damning. But, the film was called Marinetti (after F.T. Marinetti of the Italian Futurists) and it should have been obvious that it would not be an ordinary film. Following the premiere, Thoms showed “the film in other states [in Australia, and then] embarked on a world tour, determined to assess international responses to the film”. [43]. Marinetti had pretty much worn him out. [44]

The response to Marinetti marked the beginning of the end for Ubu Films which broke up in 1970 as each of the main protagonists went their separate ways. Thoms had gone

“to the US to exhibit his film Marinetti, and spent the next year screening the film in Europe, while also working for Oz, IT, and Friends magazines in London, the First International Underground Film Festival, the Wet Dream Film Festival and the Nederlandse Filmmakers Koop in Amsterdam.”[45]

He ended up in London before returning to Sydney in 1970. Meanwhile David Perry finished his film Album (April, 1970) and went to live in London. Aggy Read went on to finish “his film Infinity Girl (1971) which forms a major section of his Ubu diary film Far Be It Me From It (1968-72).” [46] And the others began working independently. Previously, in July 1969 the Sydney Filmmakers Co-op had been established despite a lack of support from the arts funding bureaucracy, though braced by the growing enthusiasm of many other young filmmakers.[47]

Perry had been “apprenticed to the printing trade” [48] in the 1950s and developed an interest in painting and photography that, coupled with his teenage interest in the movies (especially the newsreels and animation), led him to film-making. While working in the printing industry he became involved with the Sydney Push where he met Thoms, among many others. Around 1964 he joined the ABC, and his exposure to the graphic arts (printing technologies) was translated into making film. At the ABC he worked for the Federal Engineering section at their studios in Gore Hill [Sydney] in what was known as the Telerecording Department where film was used to record the ABC’s productions. This gave him access to out-of-date film and to high-grade cine equipment.

Previously, over 1967, Thoms, Perry and Read produced a number of hand-made films, which they called “synthetic films”.[49] Of these, Perry's first was Halftone (1967). The “halftone” screen is used in the printing industry (to which Perry had been apprenticed at the age of 16). [50] It is a gridded pattern of small dots, squares and lines that, in printing, is laid between a negative and the printing plate so that it converts tonal images (photographs) into patterns that although in black and white ink are sufficiently small to give the visual effect of being grey-scale.

Perry used several half-tone screens in an optical printer, directly printing them onto strips of 16mm film,

“so that [as he says] the original dot patterns were spread across the full width of the strips and thus covered the soundtrack area as well as the image area. After editing I asked the lab to run the film through the printer twice, printing the image area first, then to wind the original and print material back to the start and print the sound track area with the image starting twenty-eight frames earlier to allow for the offset between picture start and audio start on a standard sixteen millimetre print. The result was a film in which the pattern you saw on the screen also created the sound you heard from the speakers.” [51]

Thoms produced Bluto (1967) in which various instruments are used to scratch away at black film leader in lines along the frame, across the frame and loose circular movements are inscribed into the film with (according to Mudie) “a scalpel, razor blades and a needle”[52] and looking at the film myself I would suggest a very stiff (wire) brush, perhaps steel wool and a blunt-nosed nib from a calligraphic pen. The “incisions in the film are then hand-coloured with Textacolours.”53

He also made Moon Virility (1967) in which a brush is (probably) held against and dabbed in multiple coloured layers onto “a piece of clear film with an unheard optical sound track printed on it that was found in a rubbish bin” [54] as it is wound through an optical printer.

Read made Super Block High (1967) by (from the look of it) shooting in tight close-up the raster of a TV screen that has had the syncs thrown out of whack and then brushed or scraped with something like a metal comb, although Mudie indicates that it was made with a grinding wheel [55] that attacks the frame over its vertical, horizontal and diagonal axes. The film is then painted so that the edges of the scrapes show saturated colours.

Any means of affecting the film: painting on it, scratching it, damaging it, could be exploited to make synthetic film and was so for many of the films used in the Ubu lightshows. [56] As Thoms wrote in Ubu's Hand-Made Films Manifesto, which they all signed, the camera is no longer necessary, “hand-made films are abstract” and anyone has the freedom to make a film by scratching, painting, drawing, biting, chewing directly on to film or by “any technique imaginable”... “[T]hey may be projected alone, in groups, on top of each other, forward, backwards, slowly; quickly, in every possible way” … “as environments, not to be absorbed intellectually, but by all senses.” [57]

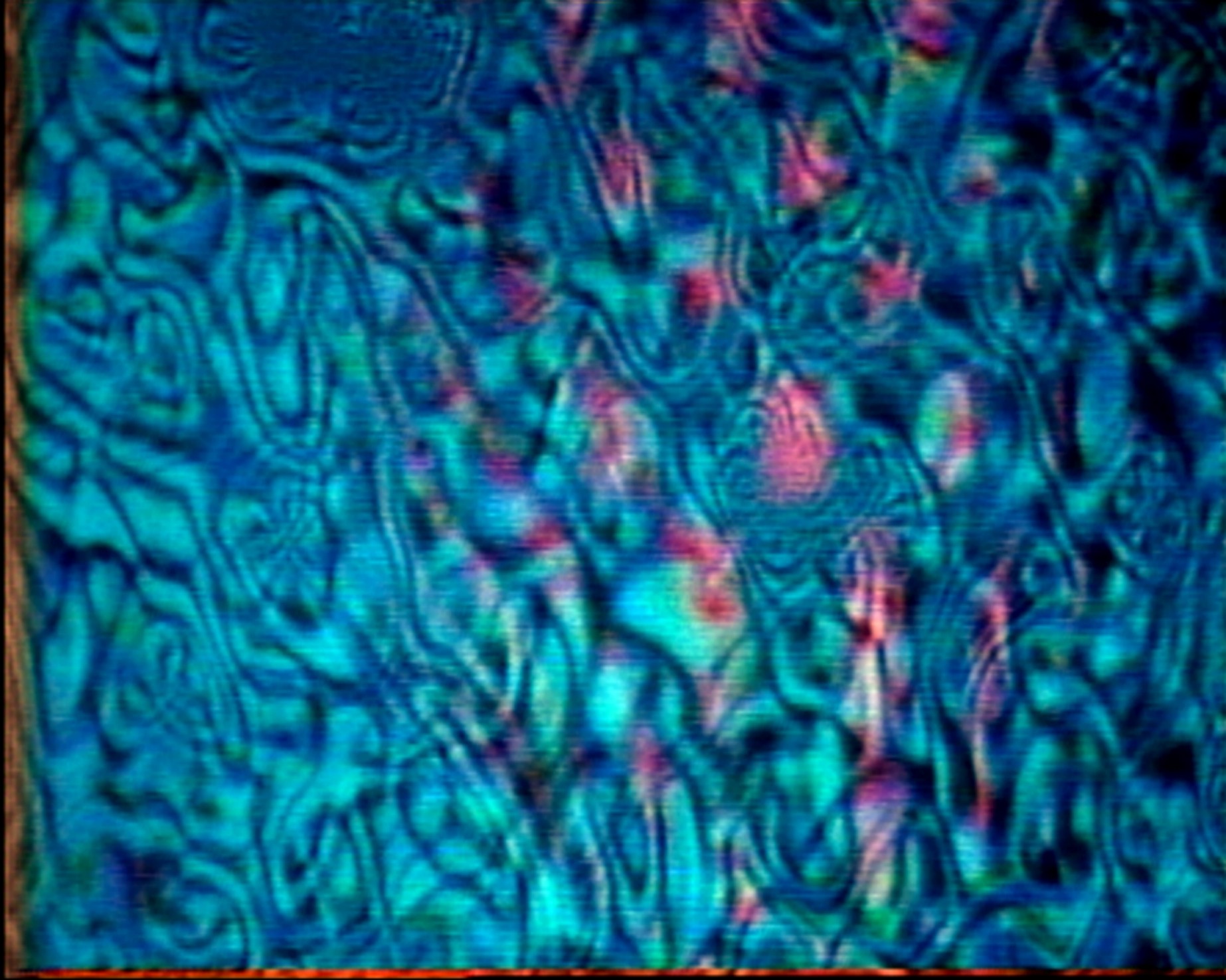

While attached to the Federal Engineering section of the ABC (at the Gore Hill studios in Sydney, c.1968), Perry had access to high-grade production equipment. This provided him with the opportunity to experiment with television (or video) as a means for making “synthetic” films, and it was there that he made his electronically sourced, synthetic, “experimental” film Mad Mesh (1968). One of the ABC’s television cameras had developed a fault with the mesh in its Image-Orthicon [58] image pick-up tube (the I-O tube) which could be moved around with magnets. The mesh in the I-O tube had become loose which meant that it could be moved around with magnets. This produced crawling, moving patterns on the monitor. Perry recorded these patterns by exposing 16mm film with red, green and blue filters in a series of multiple exposures so that they gave an irregular, fluid moiré pattern while moving randomly across each other. Occasionally this produced a full range of colours as the mesh patterns mapped onto each other through the RGB filters. The distortions were controlled by Tom McGrath and it was set to electronic music by Ken Parkyn. [59]

Although kinescoped from the output of a television camera displayed on a video monitor Perry did not think of Mad Mesh as a video work. For him it was a film, it was made with film techniques and recorded onto film and presented as such. [Fig.1] [60] So Mad Mesh was a transition work, made using electronic means but recorded to film, which in 1968 was the only way to record colour footage. Perry later commented that even while working with videotape he still saw himself as a film-maker, although he knew it was impossible to get good kinescope recordings of the video works. The texture and quality disjunctions of video and film in these attempts to make films with inappropriate equipment interested him and was “sometimes very lovely” but he really wanted to make films. [61]

Perry's last film with Ubu was a short autobiographical montage called Album (1970) made from Perry's early photographs and clips from Ubu films that he shot. It opens with a close-up of the take up rollers pulling a film through the gate of a projector followed by Perry holding an older type still camera (which appears to be a Voigtlander), the titles, and then photographs and short clips of films he had made edited together in short staccato segments as he talks about his childhood interest in photography. Farmland and the bush, flowers, photographs as a child and as a teenager are intercut with moments from Ubu films he shot that show his early sexual interests (e.g., with the dancing girls sequence from The Tribulations of Mr Dupont Nomore). Many of the images are posterised colour or other optical effects, including sequences from Halftone. He talks about being an apprenticed printer, and illustrates this with a slightly longer sequence from Halftone, more clips from (generally more conventional) film he shot, followed by his interest in light. The sequence then returns to friends, now his adult friends including Albie Thoms, and Abigail (his then wife), Liffy (his daughter with Abigail), moments in their family life from which he turns to his (semi-abstract) paintings, more flowers while thunder crashes on the soundtrack and finally a run of shorter, staccato recapitulations of images and clips from earlier in the film. [62]

Perry then moved to London.

At this point, c.1969-70 (with Challenge for Change in Canada, TVX in London, and Australians like John Kirk and David Perry living there), video begins to encroach on the film world, and it is through the experimental film-makers, community activists and hippies that it gained a productive life of its own. However, for a long time many of the film-makers saw video as the poor cousin. For a start it was only monochrome, not colour and certainly not the luscious colour of Kodachrome or of much Super-8. Neither did it have the resolution that 16mm had, though it did have a resolution similar to that of Super-8. For much of the first decade of video it was not considered useful for anything except stuff you couldn't actually do with film, among which was activist, fast turnaround community interaction and social feedback, since it did not have to be processed before you could see what had been shot. All you had to do was rewind the tape and play it back. Also the sound was automatically in sync with the pictures, which made it very useful for interviewing or recording events in which the sound had a major role.

Video's other great difference was that it was electronic, much as audio recording had been since the 1920's.[63] The electronic effects made possible with the video-mixer were readily available to the editor. Although you could do them in film it was a far more arduous (and expensive) process. Video, being an electronic medium, could also be synthesised and that, for a brief period, was its most valued capacity, since it could be composed as though it were electronic music.

At first editing video was downright impossible, leaving gaps and visually-noisy roll-in results at and after the cutting point. The timing of the edit was never really accurate and the out-point / in-point could be anything up to seconds away from where you wanted it. The editing problems were solved to a major extent by several innovations developed by community video production groups, such as the back-timing trick used by TVX [64], or the later Editape system [65] developed by the National Resources Centre at Paddington Video Access in Sydney. Once Sony got their U-matic system working and selling they then incorporated editing functions into it. By the mid-1980's the Sony VO-5800 series of U-matic video machines had become a reliable production device adopted in the, by then, remaining access centres such as Open Channel, educational institution video facilities and independent post-production facilities like Heuristic Video.

The single most important advance that made video viable was the Time-Base Corrector (or TBC) developed by Quantel [then known as Micro Consultants who developed the first integrated circuit video speed analogue-to-digital and digital-to-analogue converters, both of which they used in their TBC 2000] in 1973.[66] With this, video play-back could be easily mixed and otherwise combined with other video tape sources, the effects available in the video mixer, computer graphics and the video synthesiser. It also had the advantage of making editing just that bit more reliable.

Meanwhile, having survived the ignominy of the premiere of Marinetti, Thoms went overseas in November 1969 to show his film around the centres of the avant-garde in New York (only briefly) and Europe, ending up in Britain where he met “Hoppy” Hopkins of TVX which, Thoms comments:

“was, at that stage, ... just interviewing people. It was very basic. One time I remember they’d gone round to a place called the Arts Lab in London and the police had raided it and arrested somebody for drugs or something. And they weren’t there at the time, nor were any other television media. So they immediately re-created the event on half-inch tape and sold it to the BBC as a news thing. And so one of the first uses of half-inch video on broadcast television was this fake sort of thing of the police busting the Arts Lab. And that was the attitude of TVX; they were anarchists.” [67] [See John Kirk's version of the story above.]

While in London, Thoms worked with Richard Neville who was interested in “start[ing] a new newspaper called INK, a weekly alternative newspaper.” [68] Thoms suggested a video version of it to Hoppy, but nothing eventuated, although Thoms noted the Canadian [CFC] project. However this contact with the local underground in London led Thoms to propose and “publish [at the Isle of Wight Festival (August, 1970)] [69] a stencil-duplicated newspaper called the Freek Press about four or five times a day.” [70] Having done that, on his return to Australia “David Elfick who was the editor of Go Set asked [him] to do [something similar] for the Wallacia Festival.” [71] This resulted in a daily news sheet called Rubbish. Albie notes:

“we [in this case Thoms and Mick Glasheen] were talking about what TVX was doing and I’m pretty sure he suggested that I check out the Akai quarter-inch system. Or he'd just heard about it or something. And we decided we’d try and do something for the Wallacia Festival, which was the end of January 1971.

"I approached Akai and they were very happy to loan us a camera and a monitor and a recorder. So parallel to providing the newspaper service, we decided to have the video thing, which I’d talked about having with INK, you know. This was a live thing. .... We just interviewed people at the festival, got their opinions, played it back on the monitor outside our tent where we were producing the newspaper.” [72]

David Perry had moved to the UK in October of 1970 [73] and while there he began experimenting with video. He took a job as a technician in the Hornsey College of Art CCTV [74] studio. Knowing that he already had considerable experience in film-making his boss gave him some lecturing work in film and video production, although Perry did note that this aggravated the traditional class division of work amongst his technical colleagues. [ The college was already using industrial video equipment in its Film & Television Department and, in what is probably the first live video-process installation by an Australian artist (albeit working in Britain at the time), Perry

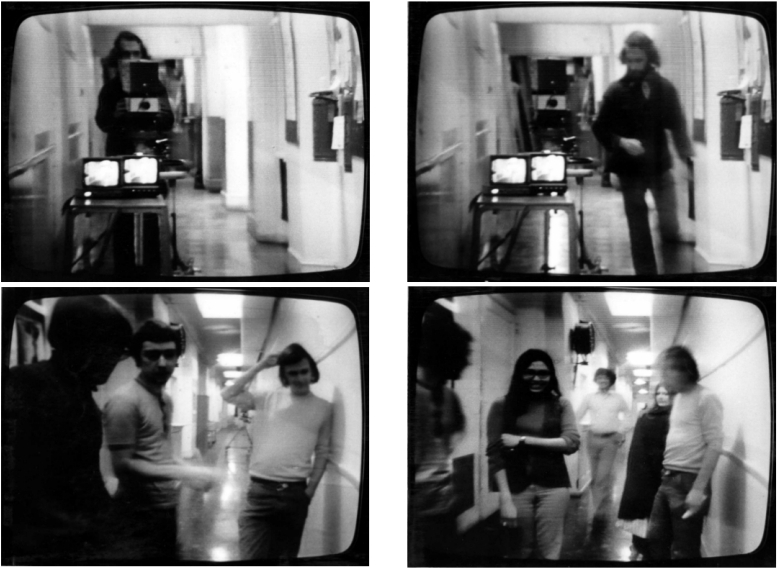

“set up a small experiment in the corridor between the Fine Art and Film & TV departments … My idea was to use a television system as an object rather than as a medium, and to see what kind of interaction (if any) would occur between the object and its observers. A camera was placed to give a static view along the corridor and of any events which might happen there. The picture was recorded to videotape for about one hour.

There are two characteristics of video as a formal medium that make it different from film. One is that it can be treated, usually in an installation situation, as an object in which the viewer enters some sort of interactive relationship with the image, or as a sculptural or painting-like object in which some prepared or pre-recorded – in those days on videotape – material is presented. [81] The other characteristic is that which I have already mentioned, namely the capacity to produce electronically generated or processed images with it as a “visual music” or for various kinds of feedback. Those feedback processes that operate over long durations bring video into the personal and social realms where it supports mnemonic and analytic practices, as well as (real-time) interactive processes as explored in Perry’s installation in the corridor.

Perry's use of video extended into the social realm where video could support analytic practices reflecting his life and ideology, and he made several such film/video transition works while living in London, two of which stand out as public expressions and at least one in which private small-scale family activity is recorded. This can be seen in a simple domestic tape of Liffy (David and Aby's daughter) just doing stuff in the backyard of their London home.

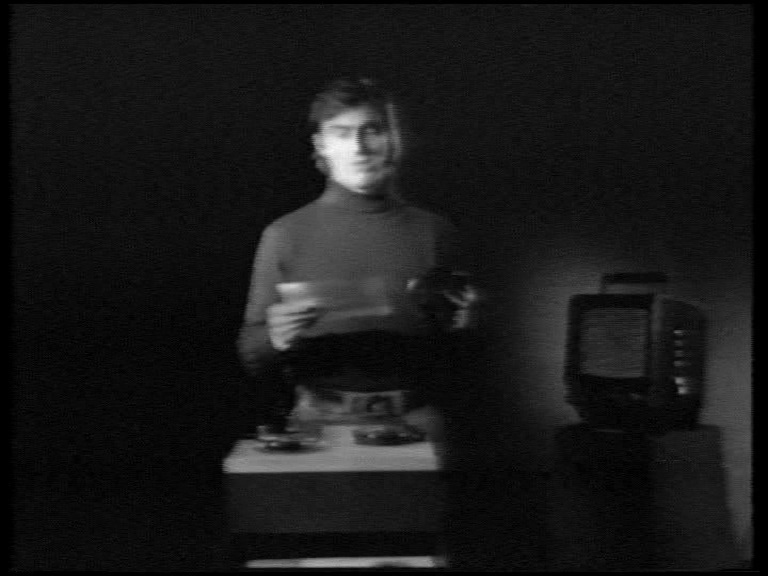

Of Perry's public expressions the first is My Dutch Newsreel (1972), which he subsequently reworked (in 1986). It was “shot in Holland during a family visit, and reflected on in London and Sydney” (thus the rework) and consists in “[l]andscape studies and the company of Clem Weight, an old friend from the Ubu days, and her new [Dutch] husband” (Theo van Leeuwin) who was also a film-maker. During the trip Perry shot 16mm film of their domestic interiors and the landscape of an island in the North Sea which they visited while there. He then added it into video of him telling the story of their holiday and it this became My Dutch Newsreel (1972). [82] [Fig.3] David speaks of the distance and isolation of living in Australia and of Australian's desire for travel. He speaks of the function of landscape in building and sustaining “the collective unconscious schema: a representation of what life's all about. [This being] the basis of all cultures.” [REF: from the video ??] That reflection (the reflection on one's self and the role of the world context – more than just the social context and perhaps not far removed from the First Australians' notion of 'country' in forming one's identity) is made manifest through the double image of the Kodachrome colour and the old monochrome video in a TV set in the scene. (The 1986 version was awarded First Prize (Video Art), in the Australian Video Festival, 1987). [Needs further description, especially the image of David on the TV screen]

This mixing of film and video seems to occur regularly in Perry’s work of the ‘70s (and through the ‘80s). In 1973 he devised a project called Utopian Memory Banks Present: Fragments From the Past, which used video footage that Perry had shot with the college portapak in the streets (of South Kensington) and the Science Museum in London. With this material he made a tape based on the idea of looking back from some future time at what had been happening in London immediately after the Paris student revolution of 1968 and the unrest in British colleges at the same time. The video was

“set in an indeterminate future after “The Interminable Struggle and The Greater London Fire”. A presenter with a burn-scarred face showed the footage I had shot as if it was material “recently discovered in the ruins of a building in old North London”.” [83] [Fig.4]

It is based on aspects of life in London as seen from an imagined future, drawn from what had been happening in a somewhat dystopian London immediately following the Paris student revolution of May 1968, the unrest in British colleges, and the anti-Vietnam War movement. Perry used material he shot at the Science Museum and around West Kensington (London) at the time, representing it as old found footage, which in its own way echoes a kind of early tourist video. The video opens to a fanfare of trumpets (which later turns out to be a pipe organ) and martial drums. A fire scarred presenter with a fey voice is shown standing at an open-reel videotape player with a small video monitor beside him. He announces that this “Collective Memory Module” offers

“for your absorption … fragments of images and sounds of London in the year 1973. They were recorded by a contemporary process known as videotape recording in the period before the interminable struggle and the Greater London fire.” [84]

These "documents" are represented as re-discovered footage, and include sections of film and Portapak-video footage used [as Perry notes REF?] to exploit the contrast in textures. [85] We are watching what might, in fact, be a message from the future set up as an attempt to bring back to the surviving population memories and examples of what London was once like – memories from our past – so that as the presenter says: “We [can] avoid at all costs the danger of collective amnesia.” [86]

This “Collective Memory Module” begins in Exhibition Road outside the Science Museum and then, in the first “module” looks at “some of the relics displayed” in the Museum, from James Watt's (though not identified as such) steam engine, other kinds of engines, to a giant model of a crystal showing its atomic structure. The presenter then reminds us that these exhibits “had been used to create considerable wealth at the time when these scenes were recorded.” In the second “module” the memory fragments step to scenes of children (including Perry's daughter, Liffey) (playing in the streets ?), old and new cars, all in a location of poverty, with people living under a freeway overpass or railway bridge in the area known as West Kensington. The presenter regularly adds to his description of these visual fragments with statements regarding the political situation underlying the general poverty of most people living in the locality (or in greater London) at the time.

In the third “module” Perry appears in front of a painting of his, reading a prepared statement the sound of which has been deliberately “erased” as though it contained politically unacceptable material. [Fig.5] A following segment shows an apparently slowed down video of a man at a piano playing, with the sounds of machine gun fire beneath it as though there might have been a civil war occurring at the time. The video closes on this last fragment as the presenter then turns off the monitor and mentions the “feelings of despair and the fear of the approaching struggle, which we know were characteristic of that period”, and finally declaiming “Long Live Utopia”, as the image fades to black.

Perry comments in his Memoirs that the result was technically very rough,[87] but given the state of the editing systems that would have then been available this is hardly surprising. However he soldiered on.

Much of his production over the next half decade worked with these mnemonic ideas, with occasional excursions into the more formal possibilities of the medium. For example, the exquisite moment encapsulated in Interior with Views (1976) which I shall discuss when we return to Perry's work, by then, back in Australia [Fig.6].

So this was a generation on the brink of change. Among those changes was the way we thought about the media, particularly television. Those of us interested in new electronic media especially video and the potential it offered for television read Radical Software, [88] the journal of the experimental video scene in the US. The journal ran from 1970 to 1974, but may not have been seen here until late 1972).

Video is the unruly child of television. It has its origins, like its parent, in the telegraph and the facsimile, not photography and film as is generally supposed. However television and video have long been conflated with film, since both are moving-image media. Perhaps this has its origins in the “midday movie” in which the presentation of narrative films became the mainstay of television.

But, this conflation became the primary way in which video is understood. For example, Lev Manovich, in his Language of New Media [89], asserts that the cinema and television/video are both representational technologies in that they create an illusion of (i.e., they “represent”) the real, although he fails to recognise the entirely different means by which each do that. The one differentiation between cinema and video that Manovich does allow is that the content of the video screen (and the radar screen) can be modified or “continually updated in real-time” [90], unlike the cinematic image which has to be set up, shot, processed, edited and printed into a sequence of unchangeable frames [except through the depredations of time], and it is these that are then projected onto a passive screen.

To cinema and television he adds computer-generated imaging (computer animation), given that they are each used to create the illusion of some sort of “reality” in the depths of the screen projection, while maintaining that cinema is the precursor and primary source of this illusionistic practice. [91] This screen projection is what I would call a “navigable space” – in that one navigates it with one's eyes and memory by looking at different objects in the screen space (as one does the outside world) and making of them what one's acculturation has established. But this is not how Manovich uses the term. [92] For Manovich a “navigable space” requires access to a database of possible (data)spaces – available, for example, in a computer game – through which one is transported with the aid of an interface. [93] It is the conversion of the content of various prior media types into the digital and the new types of space that that conversion enables, such as computer games and the Internet, that for Manovich is the crucial step to “new media” and since computer-based imaging is digital he regards it as being the overarching new medium. As Manovich puts it:

“All new media objects, whether they are created from scratch on computers or converted from analog media sources, are composed of digital code; they are numerical representations.” [94]

Thus his differentiation of new media is based on a digital, versus analogue, means of information carriage. It is, for much digital moving image work, the way in which the potential interaction is implemented.

Manovich's intent appears to have been to provide a technological history and contemporary analysis of computer imaging (in its widest possible instantiation) and to do this he has ignored aspects of analogue imaging or representation. However by ignoring the technical aspects of (analogue) television and video we also lose a variety of other ways to inquire into its aesthetics.

Manovich treats all the visual media as representational, be they cinema, television and video, or the computer image, in that they each project onto a screen,[95] which he imagines to be a kind of window frame, despite the massive technical differences between the types of screen that are the site of that projection. Through this window the viewer looks at some re-constructed reality, whether that is a representation of the place in which the film is shot, or where the news is gathered, or the TV studio, or some other real or constructed or even synthetic (i.e., generated) “location/set” wherein the “action” takes place. But the real screen is the retina in the rear of the eyeball, or perhaps even the “mind's eye” upon which we project our interpretation of what that screen (the retina) receives [and ultimately we have to acknowledge the quantum problem of whether what is actually out there is what we see, given that what we believe to be there is a construction learned through our induction into the world].

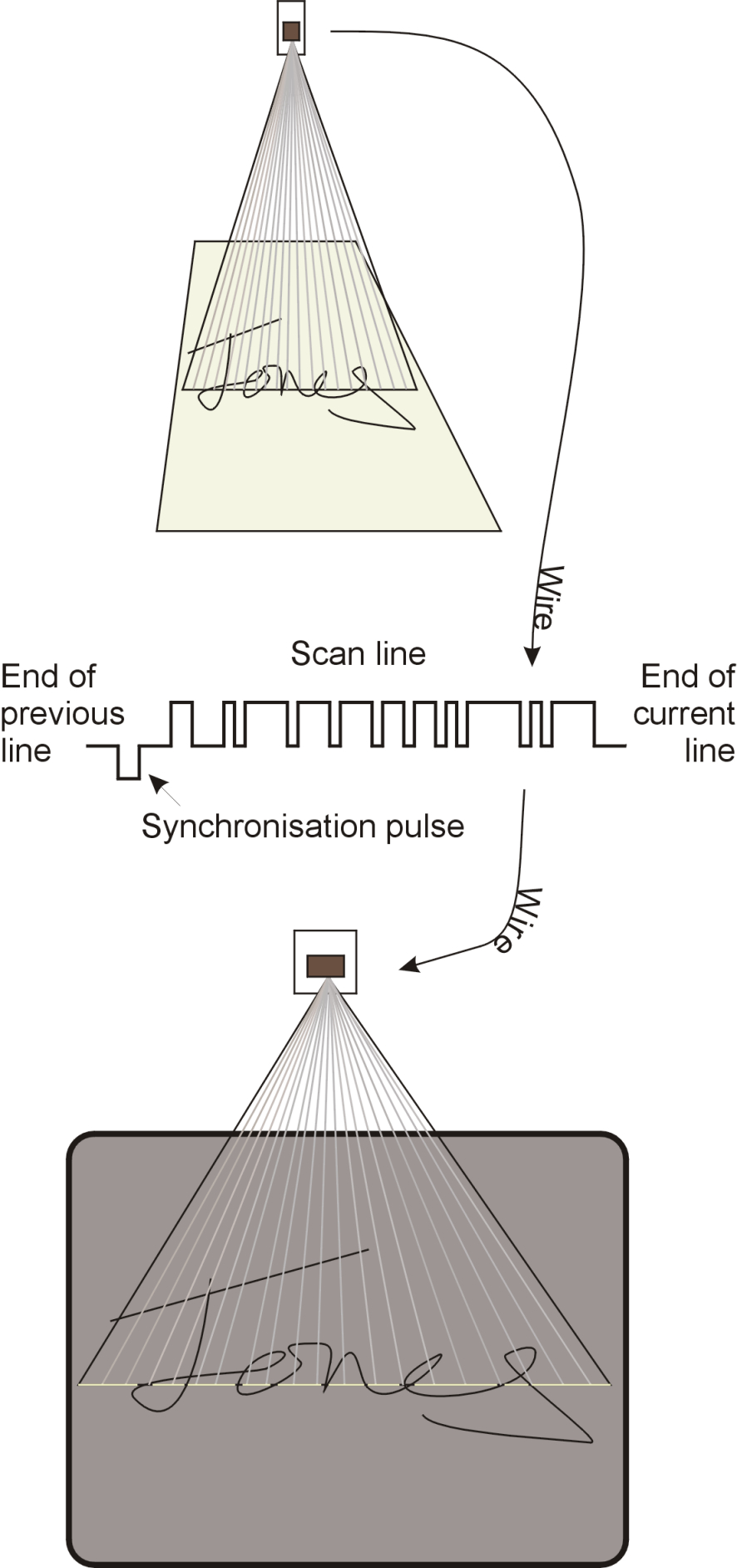

As with the retina the film or photographic image is acquired in parallel. The molecules of photosensitive material on the film (the celluloid), the photographic “plate” or in the retina are spread out (more or less) flatly across the photosensitive region with the image focussed onto it by a lens. In other words, the whole image is available at once (in a single opening of the shutter). But in analogue video or television while the image is stored in parallel on the photo-sensitive surface of the imaging tube or chip, it is then read from that surface sequentially (i.e., it is scanned), with synchronising signals driving the reading “beam” across that light sensitive surface continually reconstructing it through time, on a point-by-point basis. This is the real difference between film and video. [This is also how a computer-based scanner works in picking up images from a photographic print or similar for use in the computer, although in this case each whole line is gathered in parallel but read sequentially while the whole 2-dimensional image is scanned one line at a time.]

Another factor that we need to account for is that in the cinema the scale of both the screen and the image projected onto it promotes an identification between the viewer and the scene being projected whereas in television and video the viewer is not contained within the immersive space of the cinema and its screen and, mostly, is not led to identify with the content but is removed from it, standing in a more objective position, regardless of any objective/subjective dimension in the content. The viewer thus is in a position that allows a critical stance, a potential for disbelief.

So what Manovich has done is to separate out the digitally-encoded visual from the analogue visual, i.e., he has isolated out computer-mediated digital information from continuously variable analogue information by giving the digital forms the exclusive right to the label “new media”. However, video and film have now become almost exclusively digitally mediated as well so this division is no longer of any use. What really counts in making the attribution “new media” is whether it is chemically or electronically sourced, and the ultimate point about video art is that it is an electronic art and bears the same relation to film as electronic music bears to orchestral music. The actual medium used in (re)presenting the image is not the point, it is the means by which it is originated that counts. But, today, whether that medium is analogue or digital electronics is of little interest to the viewer given that the actual information carrier (the video) is most likely to be of digital form, and so I argue that the new media are the electronic media of which computing is but one type.

Having argued that it is electronic versus chemical mediation that counts, I will take a look at the technical aspects of this electronic medium that is video. Video is a form of writing derived from the scanning techniques developed by one Alexander Bain in the mid 19th century so as to transmit over the telegraph wire the signature of the person sending, in particular from one bank to another, the funds by which commerce could proceed. [96] [Fig.7]

Bain and other early experimenters working with the telegraph [97] discovered that, by scanning a two dimensional “image” in a line-by-line sequence it could be rendered in one dimension and transmitted down a wire. However, to re-assemble the image at the receiving end it had to be possible to know when each line finished so that the next line could be placed below it on the page. If this process of “synchronisation” is done automatically by sending a pulse down the wire at the start of every line then it can be automatically re-assembled. In this the facsimile and video are not that far from typing and computer printing in which the “carriage return” sets the printing head back to one edge of the page ready for the next line. If another, more significant pulse is sent at the start of every page then a sequence of pages, or frames as they became known since they were set by the boundaries of the picture, can be transmitted and reconstructed at the receiver. Of course the end result may well be the illusionistic image of the cinema, but its technical process offers the possibility of entirely other non-iconic (i.e., synthetic) means for making images.

It is these other means (e.g., video sculpture and video synthesis) that appear in early (i.e., 1960s and '70s) approaches to video art (independently of the opposing tendency towards documentary as an activist form) that make early video art both interesting and in its more experimental forms unrecognised (until 1973 ?? Tim Burns) within the framework of critically accepted contemporary art in Australia, although this was not so much the case in the US. [98]

Until the digital age, the scanned and reconstructed image – formed as changes in brightness (i.e., changes in the voltage) of the signal rendered onto a raster, or grid – was the standard form of tele-visual display in which the intensity of a pencil of electrons (the beam) is modulated to form a tonal image. The electron beam, when scanned across the rear (the inside) of the phosphor surface of the screen of the cathode-ray tube, inscribes the image onto it. The inscribed line then glows with light from the phosphor projecting the image onto the retina of the viewer. However the screen does not necessarily have to be scanned as a raster. In the early development of the cathode-ray oscilloscope the electron beam was moved around the phosphor screen of the tube quite freely by continuously varying the magnetic fields that focussed those electrons. The kind of image that could thus be produced is very close to writing and was known as “calligraphic”. Lissajous figures displayed on an oscilloscope are an early use of this approach. A more rigorously controlled (but still calligraphic) motion of the beam later became used in early forms of computer graphics, with the “wire-frame” image being what was most easily produced. The “calligraphic” display [99] was more commonly used for computer output because it did not require extensive computer memory to store the image while it was being read out to the screen, thus making it very much cheaper given the high cost of early forms of memory. [100] But it was also an important approach taken in early video art in the search for electronic means for directly generating abstract images (video synthesis) both in the work of some American video artists [101] and in particular for this discussion, artists working in Australia (e.g., Stan Ostoja-Kotkowski or John Hansen) who explored the television set, and later video as well as electronic music.

The inscription of the electron beam onto the screen of the display makes video a one-dimensional stream of information and, given that the raster of standard television and tonal bit-mapped computer graphics, is a special form of Lissajous figure, all (analogue) video is actually more a form of writing [102] than it is photography. We can see this especially in Ostoja-Kotkowski’s electronic drawing and Hansen's video synthesis and Bush Video’s video feedback work, both in Australia. [103]

So the upshot of all this is that as non-broadcast television, video possesses characteristics which, when recognised, show it to be a very different medium from the colonised form that television has taken in recent years.

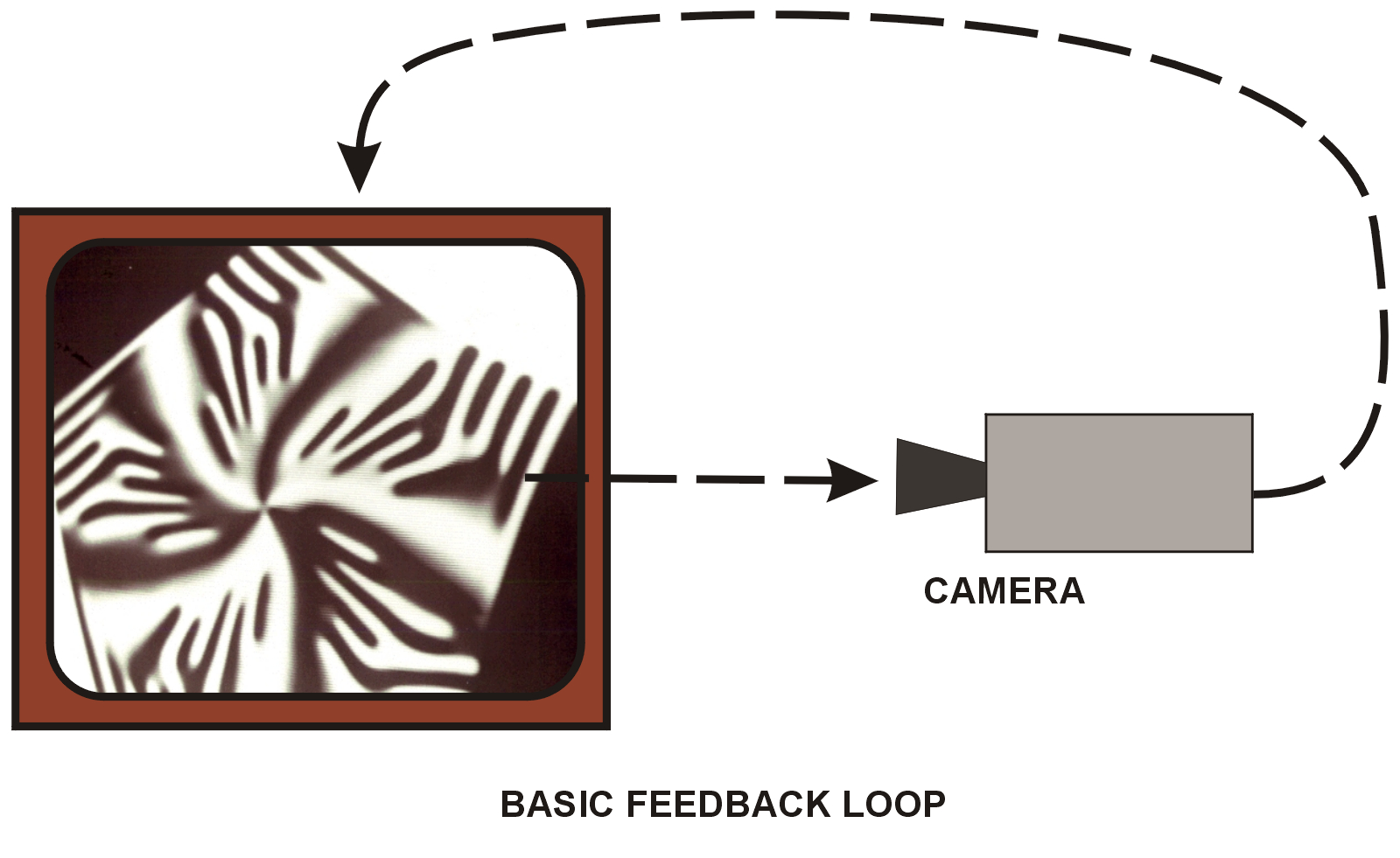

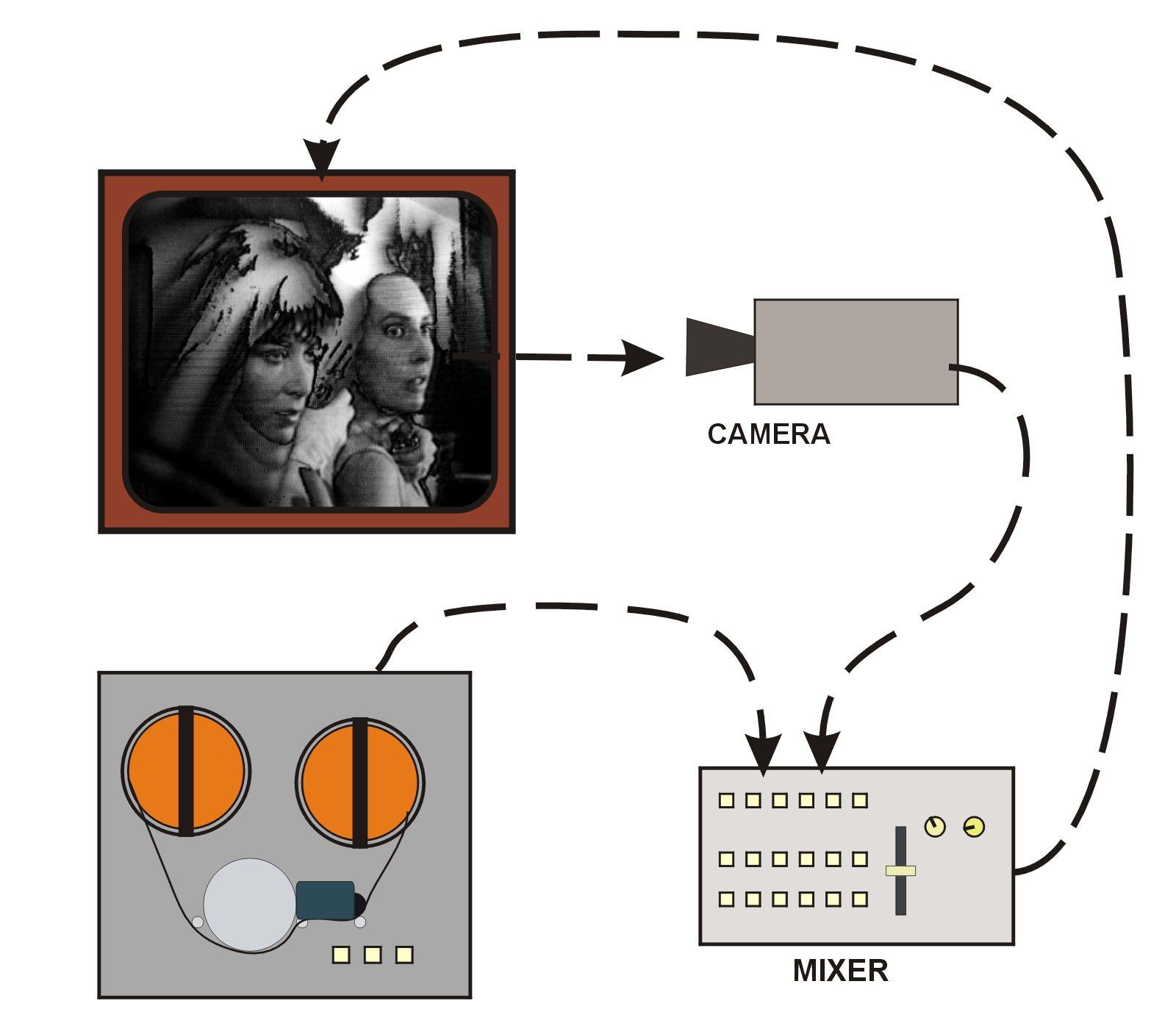

One aspect of video that renders it significantly different from film and television is its immediacy: you don’t have to wait for it to be processed before you can see the image. Because the video signal is electronic, it can generate live or real-time images that do not have to be recorded. This liveness can offer a, what I will call here, “turn-around time” of microseconds. That is, video has a capacity to provide instant feedback [Fig.10] of its content for further intervention. Feedback, in its several forms, can take from microseconds to as long as one wants to hold on to the signal (supposing one records it by writing it to tape or disc, or now-days, computer memory). [Fig.11]

It is the turn-around of the video signal that is the significant factor in its use as a reflection on both itself and its content in video synthesis and its use in the longer turn-around time processes of socio-political feedback situations, for example as used in performance training and in social analysis and activism.

Thus feedback is a form of memory, a holding on to current information for analysis or for comparison with future information. Just as in psychology memory is divided into short-term and long-term memory, so we can see a division in the ways that video is used based on the duration of the feedback cycle. Short-term feedback cycles produce a kind of image that is commonly used in what I call synthetic video, while long-term feedback cycles produce the kind of memory that we normally think of as being something that we use to communicate with others about things that are of common concern or interest. In the period under discussion here, this came under the general rubric of documentation, whether it was of a performance art work or of a politically potent activity within some community; the only differences in these latter being the intentions of the author(s) and how much editing might be thought necessary. Fast turn-around feedback cycles tend towards the formalist or abstract in aesthetic terms, whereas the long-term feedback cycle correlates with the use of video as a recorder of images that are figurative rather than abstract.

The implication of these turn-around cycles and their durations is that video is first and foremost a process-based art, and it is this aspect of video as process that was a hallmark of much early video art produced in the US and appears to some extent in the more synthetic and meditative works of Bush Video and several other early Australian video artists. But Bush Video’s synthetic works are also perhaps among the best examples of video as a kind of writing.

Where the feedback cycle is irrelevant to the work, then it returns to the filmic (illusionistic) role to which much contemporary video art has fallen, simply being a presentation of some pre-structured narrative, essentially cinema but produced on video simply because of its accessibility.

Ultimately, especially during this period when video art was in its infancy, it was the cost factor that was its most problematic and most limiting characteristic. Much of the early video art existed in a culture of limited means. The fact that one could make moving pictures (albeit monochrome) and show them to others without having to raise the thousands of dollars necessary to make a film or a television program was, often enough, all that was needed, especially for activist purposes. If you really wanted colour video it was possible to get sponsorship.

The first provision for the funding of experimental film was made through the announcement in August 1969, by the then Prime Minister John Gorton, of the Experimental Film [and Television] Fund (EFTF) [104] and its first call for applications in April 1970. At that time it was administered by the Australian Film Institute (AFI)] with funding from the Film and Television Board [later the Film, Radio and Television Board] of the Australian Council for the Arts.[105]

There then began a complex (and difficult to untangle) series of re-structurings in which a number of bodies charged with supporting the growth of the film and television industry in Australia came and went. One early body was the Australian Film and Television School which was broached in 1969, shelved for several years and then actually established in 1973.[106] The third (February 1972) report of its planning body, the Interim Council for the National Film and Television Training School, notes that it had taken over the “programmes initiated by the Australian Council for the Arts”

In January 1973 the then Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam, announced that the Australian Council for the Arts would be re-structured as a statutory authority to be known as the Australia Council. The Film and Television Board was established within the Australia Council and took over the administration of three funds: the Experimental Film and Television Fund (EFTF), the Film and Television Development Fund and a General Production Fund.[107] However the EFTF remained under the administrative control of the Australian Film Institute

In February 1974 the Film and Television Board announced that it was “about to help launch a series of public access TV centres”. A press report by Ian Moffitt in The Australian of 18th February 1974 under the banner “Channel Everyman”, notes that

“The public access concept – or compromise copies of it – are sparking excitement in the media. A visiting BBC expert lectured on the subject last week …

In 1975 the Labor (Whitlam) Government re-organised everything again: creating the Australian Film Commission (AFC), which was to “handle all aspects of government funding for film and television, apart from the Australia Film and Television School”.[109] Then, after the dismissal of the Whitlam government in November 1975, the incoming Fraser government decided that all funding for film (and, by default, video) production, distribution and exhibition would be handled by the AFC. Thus “in late 1976 the functions of the Film, Radio and Television Board were transferred from the Australia Council to the AFC” including the EFTF, the Australian Film Institute (AFI) and the Video Access Centres.[110]

The video access centres were transferred to the AFC and pretty much told to look after their own funding. The EFTF was transferred to the newly set up Creative Development Branch of the AFC along with the Film Production Fund and the Script Development Fund.[111] But, as Megan McMurchy has noted, this brought a shift in emphasis from creative film-making to the needs of 'industry' despite the act of Parliament that set up the AFC “requiring it to give 'special attention to the encouragement of … the making of experimental programs and programs of a high degree of creativity'.”[112]

However, ultimately it was the Film and Television Board of the Australia Council, over the period from 1973-1976 that made the big difference in the possibilities, especially with its establishment of the Video Access Centres in each of the major cities and some of the more culturally impoverished regions where the need for a community voice was seen to be of value. I will discuss the establishment of the Video Access Centres in more detail below, however it is in Video Access that the social feedback potential of video was seen to be of considerable importance.

3 Mai Elliott, RAND in Southeast Asia: A History of the Vietnam War Era, (2010) Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. RAND Corporation's Herman Kahn was the source for Kubrick's 1964 film Dr. Stangelove or: How I Learned to Worrying and Love the Bomb. See <

http://mentalfloss.com/article/22120/rand-corporation-think-tank-controls-america >

4 Wiener, Norbert (1950) The Human Use of Human Beings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

5

See Ruskin, John, Unto This Last, Four Essays on the First Principles of Political Economy. London: Smith, Elder and Co., 65, Cornhill, 1862, available at <

>, and

8 Paul McGillick, “The Institute of Contemporary Art Central Street Gallery”, Art Network, #6, Winter 1982, pp.48-49. Available at < https://allconference.org.au/library/alternative-space

9 Kenyon, T. (1995). Under a hot tin roof: art, passion and politics at the Tin Sheds Art Workshops. Sydney: State Library of New South Wales Press.

10 A group of libertarian intellectuals who mostly gathered at the Royal George Hotel in Sydney. Germaine Greer and Paddy McGuines were both members for some of its existence. See Coombs, Anne (1996) Sex and Anarchy: The life and death of the Sydney Push, Ringwood, Vic.: Viking;

and Franklin,

James, (2003) Corrupting the Youth: A History of Australian Philosophy, Sydney, Macleay Press, ch.5: “The Push and Critical Drinkers”, available at <http://web.maths.unsw.edu.au/~jim/push.html >.

11 Essentially an anti-Vietnam War and anti-conscription movement.

12 McLuhan, Marshall, (1964) Understanding media: The Extensions of Man,

London, Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd.

13 Roszak, Theodore, (1970), The Making of a Counter Culture : Reflections on the Technocratic Society and its Youthful Opposition, London, Faber and Faber

14 Fuller, R. Buckminster (1970), Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, New York, Pocket Books.

15 Lye had lived in Sydney in the early 1920s and has said that he learned

film animation in Sydney in 1921, see Lye in Film Culture 29, 1963 - ‘Sydney, Australia, was where I first learned animation ... [and] in 1921, I experimented with painting on film’. See also Thoms, Albie (1978) Polemics for a New Cinema, Sydney: Wild & Woolley, p.77. 16 Horrocks, Roger, Len Lye: a biography, Auckland University Press, Auckland, NZ, 2001, pp.54-56.

17 Len Lye in 'Ray Thorburn interviews Len Lye', Art International, XIX (April), 64-68, 1975, p.65.

18 Roger Horrocks, “Swinging the Lambeth Walk: The Hand of the Filmmaker” in Tyler Cann & Wystan Curnow (eds) Len Lye, Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne, 2009, p.25. Horrocks has drawn this from Len Lye: 'Notes on a Short Colour Film' in Curnow and Horrocks (eds), “Figures of Motion: Selected Writings” p.28. The last sentence is a modified version of Horrocks' version.

19 Cantrill, Senses of Cinema, op cit.

20 To a large extent this was the line led by Bernard Smith in his Antipodean Manifesto, part of the catalogue for the exhibition Antipodeans held 4th - 15th August, 1959 by the Victorian Artists’ Society. These debates are well covered in Burn, Ian; Lendon, Nigel; Merewether, Charles and Stephen, Ann (1988) The

Necessity of Australian Art – An essay about interpretation, Sydney: Power Publications, p.74, note 10. 21 As manifested in the controversies over Australian representation in the early (76 and 79) Sydney Biennales. Binns, Vivienne; Milliss, Ian; et alia (eds) (1979) Sydney Biennale – White Elephant or Red Herring : Comments from the Art Community Sydney: Alexander Mackie C.A.E. Student Representative Council.

22 Bernard Smith – The Antipodeans

23 The term was first used by A.A. Phillips in an article for Meanjin, Summer 1950. See also Phillips, A. A. (1958) The Australian Tradition, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press., p.89; 24 Phillips, op cit., quoted in Burn et al, 1988, op cit, p.77.

25 For example, as taught by the architect Bill Lucas at the UNSW Architecture school.

26 See the article onOZ magazine at

MILESAGO - Media - Press <http://www.milesago.com/press/oz.htm>

27 It is difficult, at this point, to discover whether this was a Sony AV-3400, which is said to have been first released in 1969 (although others say 1970, see for example:

http://www.mediafactory.org.au/kaifeng-wang/files/2014/03/Museum-of-vintage-reel-to-reel-video-recorders.-Open-reel-black-and-white-antique-video-recorders.-1ej49rj.pdf, or a Sony DV4000 which had been released in 1967. There again it could have been the Akai 1/4” portapak (released in 1969) and Albie has just remembered the Sony because it became the more ubiquitous. There was certainly an Akai around Sydney University in the very early '70s because it was used to record some of Philippa Cullen's performances in 1972.

28 Thoms, Albie, recorded conversation with Stephen Jones, 27 Dec, 2010.

29 ibid, p.56.

30 Thoms, Albie (1965) The Theatre of Cruelty, programme for performances at the Sydney University Union Theatre, July 2,3, 7-10, 1965, produced by Albie Thoms. Sydney: Sydney University Dramatic Society. 31 Poem 25, based on a poem by Kurt Schwitters, was screened as a performance piece as part of The Theatre of Cruelty. It was a form of “expanded cinema” in which an actor spoke the numbers out loudly while standing in front of the film projection screen - the actor couldn’t see the film, so had to remember the string of numbers which were not in “numerical order”. [Perry, conversation, 22/4/05.]

32 Mudie, Peter (1997) UBU Films: Sydney Underground Movies, 1965-1970, Sydney: UNSW Press, p.26.

33 Thoms, 1978, op cit, p.79.

34 Mudie, 1997, op cit.

35 “New American Cinema” toured with Two Decades of American Painting and was shown in the Qantas Theatrette, Sydney, in July 1967. It featured films by Stan Brakhage and Maya Deren [Mudie, 1967, op cit, p.71; Lawson, Sylvia (1967) “The Personal Film” in The Nation, 112, August 1967].

36 New American Cinema was shown in association with Two Decades of American Painting at the AGNSW [Rasmussen, 1967] which offered a rare opportunity for the public to see Abstract Expressionist, Geometric Abstraction and Pop Art paintings by well known American painters. The show was sponsored by the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York and supported in Australia by the US Information Service and the US Ambassador. It was at about this time that the journal Encounter was exposed as being funded by the CIA and this led many to argue that the presentation of these exhibitions were supported by CIA

funding. Such arguments were of course dismissed as Conspiracy Theories. However in a well documented book first published in 1999 and reprinted recently, Frances Stonor Saunders’ Who Paid the Piper: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War (London: Granta Books), the author argues that the CIA were deeply embedded in the organisation and funding of many cultural agencies (especially the Berlin based Congress for

Cultural Freedom) during the Cold War and that the MOMA was chief among these, under its patronage by Nelson D. Rockefeller. As the funding for Two Decades of American Painting originally came from the MOMA and the Rockefeller fund it seems reasonable to suppose that this exhibition was also part of the US foreign policy campaign covertly funded by the CIA. See Saunders, or several reviews of it: James Petras’ “The CIA and the Cultural Cold War Revisited” available at http://www.mltoday.com/Pages/BooksReviews/Review-Saunders.html, or Louis Menand’s “Unpopular Front: American art and the Cold War” in New Yorker, 17 October, 2005, available at http://www.newyorker.com/critics/atlarge/?051017crat_atlarge.

37 Time (1967) “Art of Light & Lunacy: The New Underground Films” Time magazine, February 17, 1967, pp.57-60, (no byline).

38 Kroll, Jack (1967) “Up From the Underground” Newsweek magazine, February 13, 1967, pp.49-51.

39 Thoms, email, 3/5/06; Mudie, 1997, op cit, p.56.

40 Peter Mudie, Sydney Underground Movies: Ubu Films, Sydney, UNSW Press, 1997, p.88.

41 Peter Mudie, 1997, op cit., p.59. Mudie lists Ubu's Experimental Film and Underground Movies, at the Union Theatre (University of Sydney), March 19, 1967.

42 Thoms, 1978, op cit, p.82.

43 Ibid.

44 See Thoms, 1978, op cit, pp.94-98 for the full story of Marinetti. Also see Mudie, 1997, op cit, numerous pages.

45 Thoms, Albie, Albie Thoms in Scanlines http://scanlines.net/person/albie-thoms

46 Ibid.

47 Mudie, 1997, op cit, pp.13-17; p.74.

48 Perry, David (2004), Memoirs of a Dedicated Amateur. Self-published, Sydney: David Perry, p.4.

49 Perry, David, (2004), op cit, p.71.

50 Perry, David, (2004), op cit, p.4.

51 Perry, David, (2004), op cit, p.71. See also Mudie, 1997, op cit, pp.47-8.

52 Mudie, Peter, (1997) op cit, p.45.

53 Ibid.

54 Mudie, Peter, (1997) op cit., p.77.

55 Ibid.

56 Mudie, 1997, op cit, p.12 and note 19, p.19.

57 There is a copy of the manifesto in Mudie, Peter, (1997) op cit, p.77

58 For details on the Image-Orthicon image pick-up tube, see < http://www.r-type.org/articles/art-141.htm >. Retrieved 23/01/2017.

59 Mudie, 1997, op cit, p.97, and see picture on p.98 and the National Film Theatre Programme Notes p.260.

60 Perry, conversation, 22/4/05

61 David Perry, notes from a conversation with the author on 22nd

April, 2005.

62 Perry, David, (2004) Sydney, David Perry, Memoirs. Mosman. Draft copy given to Stephen Jones (2010), p.98.

63 Wikipedia: Sound recording and reproduction. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sound_recording_and_reproduction. Accessed 1/2/2018

64 See the CATS Video manual.

65 Author unknown (probably Mario Fairlie), “The Editape 3670 Editing System”, City Video, vol.1, no.1, Paddington Town Hall Trust for the Paddington Video Resource Centre, 445 Oxford St, Paddington. 1976.

66 The first TBC I saw was at the Paddington Video Access Centre in 1976. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantel.

67 Thoms, conversation with the author, op.cit.

68 Thoms, conversation with the author, op.cit.

70 Thoms, conversation with the author, op.cit.

71 Thoms, conversation with the author, op.cit.

72 Thoms, conversation with the author, op.cit.

73 Peter Mudie, Sydney Underground Movies: Ubu Films, Sydney,

UNSW Press, 1997, p.262.

74 Closed Circuit Television.

75 Perry, 2004, op cit, p.112. This is the way Perry puts it, but Thoms (in an email of 3 May, 2006) points out that Hornsey College had been one of the first to go on strike during the student unrest of 1968 and was black banned by the teachers’ union, so when Perry accepted the teaching work he became, albeit unwittingly, a strike-breaker.

76 Perry, conversation, 22/4/05.

77 David Perry, Memoirs of a Dedicated Amateur, Valentine Press, Bellingen, NSW, 2014, p.121.

78 David Perry, Memoirs of a Dedicated Amateur, Valentine Press, Bellingen, NSW, 2014, p.119.

79 Schneider, Ira and Korot, Beryl (eds) (1976) Video Art: An Anthology, New York: Harcourt, Brace and Jovanovich, pp.240-1.

80 David Perry, notes from a conversation with the author, 2005.

81 The difference between a sculptural object and an installation can become pretty thin in contemporary art, so this difference might be considered artificial by some critics.

82 My Dutch Newsreel – 1972 and reworked 1986 – 16mm film and videotape; 5 minutes. Landscape studies shot in Holland and reflected on in London and Sydney. [Perry, 2004, op cit, p.125-6]

83 Perry, 2004, op cit, pp.135-6.

84 Transcribed from the video Utopian Memory Banks… (1973)

85 David Perry, Stephen Jones, David Perry, <http://scanlines.net/person/david-perry > and <

http://scanlines.net/object/utopian-memory-banks-present-fragments-past

>. Retrieved 25/01/2017. 86

Transcribed from the video Utopian Memory Banks …

(1973) 87

Perry, 2004, op

cit, p.135. 89

Manovich, Lev (2001) The

Language of New Media,

Leonardo Books series, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press 90

Manovich, 2001, p.99. 91

Compare Manovich, 2001, p51. Manovich notes that all new media are

re-presentations of discretised, i.e., sampled, events,

whether those samples are temporally or spatially distributed. In

fact even the spatially distributed samples are discretised over

time, whether the clocking through addresses of each pixel as it is

presented or the stepping through the lines of a video frame or the

stepping through frames in film.

92

Manovich, 2001, p.244ff. 93

Manovich, 2001, p.250-1. 94

Manovich, 2001, p.49. 95

Manovich, 2001, p.16. 96

See Standage,

Tom (1998), The

Victorian Internet: the remarkable story of the telegraph and the

nineteenth century’s online pioneers.

London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1998.;

See

also Sabine, Robert (1867) The

Electric Telegraph,

London: Virtue Bros., and

Jones,

Stephen (2005), Incunabula

of Computing and Computer Graphics,

Sydney: Stephen Jones (privately published) particularly

the section on the facsimile.

[This may be obtained from Stephen Jones] 97

Beginning with Alexander Bain in 1843, but

working through all the pioneers of the electric telescope; Nipkow

through to Baird and Zworykin and on to modern broadcast television.

See Jones, 2005, op cit,

on the Incunabula of computing. 98

In the US numerous articles and books covering all forms of video

art were published, including the journal Radical Software

and Michael Shamberg’s Guerrilla Television [Shamberg,

Michael and Raindance Corporation (1971) Guerrilla

Television,

New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.].

Paik’s eccentric persona would have contributed to this but

the cultures of New York and Los Angeles were always open to the

technologically new and innovative. Not that we weren’t here

but the art world seems to have been rather more reluctant to

embrace technological forms. 99

Also known as the vector display. The notion

behind the calligraphic display is that it is written or drawn by a

“pencil”, or beam, of electrons. This usage, the pencil,

goes back at least as far as Newton’s experiments on the

constitution of light wherein he allowed a “pencil of light”

to travel through a prism so that it was split revealing the

spectrum of colours from which it was made.

100

It was only in the later 1970s, with the development of cheaper

memory, that the raster scan was used.

101

In particular, users of video synthesisers like the Paik-Abe video

synthesiser, the Rutt-Etra and the Scanimate.

102

And it’s probably not unreasonable to suggest that writing is

in fact a specialised form of drawing, given the role of

hieroglyphics and the ideograph in the history of writing.

103

And as Albie Thoms of Ubu Films, which we shall meet later, notes:

“there were a number of times in Yellow TV (which we

shall also discuss below) when the camera operator pointed the

camera at a light and proceeded to write with the light. In one

instance this resulted in a ‘burn’ on the picture tube,

which would have needed 12 hrs pointed at a white wall to eradicate,

so it was left to mar subsequent video pictures, an unfortunate

decision, but one in keeping with the ‘anything goes’

attitude of the times [Thoms,

conversation, 3/5/05].

104

See the Press release – Canberra, Sydney, 3 December 1969:

Recommendations of the Australian Council for the Arts for 1969/1970

– Statement by the Prime Minister, Mr. John Gorton, [in

particular p.3]. NAA: A5915, 743

105

Annette Blonski, Barbara Creed, Freda Freiberg, eds.,

Don't Shoot Darling!: Women's Independent Filmmaking in Australia,

(1987) Greenhouse Publications, Richmond, VIC, Australia. p.45.

Alex

Gerbaz,

The

legacy of the Experimental Film and Television Fund, 1970–78,

a

paper given by National

Archives of Australia, Canberra, 13 October 2009

<

http://www.naa.gov.au/collection/publications/papers-and-podcasts/social-history/gerbax-transcript.aspx

>

106

Annette

Blonski, Barbara Creed, Freda Freiberg, op

cit,

p.46.

107

Official

Year Book of Australia, Issue 60, 1974, Australian

Bureau of Statistics, Canberra. p.1022.

108

Ian

Moffitt, “Channel Everyman”, The

Australian,

18

Feb, 1974, p.12.

109

Annette

Blonski, Barbara Creed, Freda Freiberg, op

cit,

p.46.

110

Megan

McMurchy, “The Creative Development Fund 1978-88: Breeding

Ground for an Industry, or Seed-Bed of Invention?”, in Megan

McMurchy and Jennifer Scott (eds), Signs

of Independents Ten Years of the Creative Development Fund,

Australian Film Commission, Sydney, December, 1988. p.3.

111

Alex

Gerbaz,

op

cit. Lisa

French and Mark Poole, “Passionate amateurs: The experimental

film and television fund and modernist film practice in Australia”,

Studies

in Australasian Cinema, Vol.5,

no.2, pp.171-184. <

https://researchbank.rmit.edu.au/eserv/rmit:13600/f2006028698.pdf

> Annette

Blonski, Barbara Creed, Freda Freiberg, op

cit,

p.46.

112

Megan

McMurchy and Jennifer Scott , op cit, p.3.

“But it occurred to me while we were doing that, that you could go a lot further. So the following year I got one of my first directing jobs, and I was directing a TV series called Contrabandits (1967). It was a cops and robbers sort of thing. And I started recording the segments and then transferring some of the things onto a second machine and mixing them through a vision mixer back in the studio.

“It was very complex, you had to get all these departments to agree, and that. But anyway we were able to remix the programs and so I could get dissolves between scenes and things, up till then it was just butt edits, right. Then it occurred to me also that I could mix the soundtrack. If I could find the time when three machines were available, I could lift the sound off, remix it and re-stripe it, right.

“So I was able to do a lot of stuff then that was new to the ABC. I suspect that other people had long before discovered it and – but basically they had a pretty conservative attitude to videotape. It was just mainly a recording device, you know. And because the two-inch tapes were horribly expensive, they were reusing them, so that they were wiping the programs. Luckily they were kinescoping some of them and some of them were preserved. But basically they had very few tapes.

“Then as the ABC’s programming schedules increased, they were putting more and more stuff to air off videotape, and it suddenly became very difficult to get machine time. And that little window of opportunity closed down a bit then.

“But with that video training... I was still mainly working in film both at the ABC, and then of course with Ubu, which was running parallel to that. Then we read about the new Sony half-inch machines that were going to become available.

“But I hadn’t got too excited about that, mainly due to David Perry. He reckoned that the resolution was going to be so poor that it’s not going to compete with film and it’s not going to… We’d actually been thinking of putting some of our films onto super-8 and trying to sell them as home… the way they sell DVDs now, you know. But because very few people had a super-8 projector with sound there was not much point. We’d be selling mute copies of our films and we abandoned that. And I thought maybe video is going to be the way. But David was doubtful.

“My first encounter with the actual half-inch Sony Portapak [27] was in 1969 and Phil Noyce had it at Sydney University. Sydney University had by then set up a closed circuit TV thing for lectures, and I don’t know who it was who'd acquired this, whether it was the film society or whether it was the university television service. But someone had acquired a half-inch machine. And when I showed Marinetti at the law school in the city, he did an interview with me on the portapak, and then played it through the closed circuit to promote the screening. And it was much better than I’d thought in terms of quality and all that.” [28]

David Perry

The intersection with Video

Fig.1: Still frame from David Perry's Mad Mesh (1968). [Courtesy: David Perry]

“When the recording was complete I placed [...] two monitors on a table just in front of the camera and connected the output of the camera to one monitor and the output of the recorder to the other and replayed the tape. This meant that I was showing pictures of present events on one monitor and past events on the other, although both sets of events occurred in identical picture spaces.

“The effect of this was that as people walked toward the installation they could see their own picture on one monitor while on the other it might be somebody else's picture or just the empty corridor. “… several people became intrigued by it and eventually a large group gathered and obviously found it engaging.” [78] This simple formalist installation [Fig.2], was not dissimilar to Bruce Nauman’s Live Taped Video Corridor piece (1969-70). [79] It provided Perry's students with what was, for them at least, an as yet previously un-encountered experience of the past injected into the present, in which the multiple layers of memory immanent in the video system were exploited as interactive processes. [80]

Fig.2: Four frames from David Perry's Corridor video installation piece.

Fig.3: Perry on screen telling the story in My Dutch Newsreel. [Courtesy: David Perry]

Fig.4: Still frame from United Memory Banks Present: Fragments from the Past (1973)

with the narrator at a half inch video player and holding a reel of tape. [Courtesy: David Perry].

Fig.5: Still frame from United Memory Banks Present: Fragments from the Past (1973)

with Perry reading his prepared statement while standing in front of a painting by him. [Courtesy: David Perry].

Fig.6: Frame from Interior with Views (1975) [Courtesy: David Perry]

Video is not Film

Fig.7: The raster scan as it applied to the

facsimile, television and effectively the

printer. [Graphic: Stephen Jones]

Video as memory

Fig.8: Video feedback in which the turn around time is in

the microseconds. The image is strictly a result of the energy in the system.

[Graphic: Stephen Jones].

Fig.9: By mixing in another image source the feedback image

produces multiple echoes of the new source. Luminance keying works well here.

[Graphic: Stephen Jones].

[Find: Shining a Light: 50 Years of the Australian Film Institute (French and Poole 2009)]

“Bush Video, Sydney's alternative TV group, claims it is making “the possible TV of the future” when cable TV subscribers select programs from a central computer bank of tapes. It is trail blazing in audio-visual processes.

“The Australian Post Office and the Department of the Media examined the future Australian cable system at their national telecommunications plan seminar last week in Sydney. Sound and vision will connect to homes like gas, electricity and phones.

“ … The initial blueprint is for “storefont videotape centres” which will encourage people to use, not merely receive, television.

“No cable networks will screen their images around the nation. They will screen their own efforts in the centres, or before council meetings, government enquiries, community groups or commercial channels which might air them for outsiders.

…

“The plan is to establish community access video centres, including a national video resource centre in Sydney which will incorporate a library, cinema, restaurant, editing rooms and community baby health centre. A small staff will guide the amateurs and edit their work.

“Melbourne will have a centre in Carlton (in collaboration with the Australian Union of Students) and further satellite-type centres will spring up in Sydney, Melbourne, Whyalla, Fremantle and Brisbane.

“Sydney's proposed centres, in co-operation with the Department of Urban and Regional Development, will be in the fast growing Parramatta, Blacktown and Liverpool-Fairfield districts and Victoria's Altona and Footscray. Groups of individuals will use portable video recorders under the guidance of a centre director.

“It's an exciting prospect. The Australian Film Institute will set up the centres in a 12-month pilot scheme and groups are already clamoring to use them as sociological tools to strengthen their communities.”[108]

Endnotes